Be disinclined to acquiesce

Advertising’s War on Consent

Consenting to sharing your personal data with a third party is not a problem that the Internet invented for us: social scientists have been struggling with the issue in their experiments for decades. Macartan Humphreys’s “Reflections on the Ethics of Social Experimentation” that provides a framework within which to consider the consent of populations being studied lists no fewer than eight consent strategies and the ethical considerations that surround them. True to style, the Internet just came along and made things bigger.

Consent matters. If I am about to collect sensitive information about you, I should make sure you know what I'm getting, what I will do with it, and why I'm capturing that data in the first place.

Consent, however, is brittle. The naïve approach to the collection of personal information is that, like for sex, consent should always be obtained before the fact. There's a snag though: the modern (and in my opinion correct) definition of personal data is very broad, covering any identifier or property relating to a person. Should consent be involved every time such data is shared? On the Web, personal data is broadcast constantly in the form of one's IP address (without which there is no networking) and sundry other fragments of information shared by the browser, well before anything that one would describe as "tracking" is involved. Even without approaching the extreme of asking for consent each time an IP connection is established, if one is not careful it is easy to come up with rules that require constant prompting.

Asking for consent too often leads to a well-known problem called consent fatigue. Imagine interacting with a child: “Can I use this Lego brick? What about this one? Can I put the green one on the red one? Can I add an antenna to the spaceship? Can I jump out the window? Can I use the yellow wheels?” It's easy to see how you would slip into okaying the one question you shouldn't. Before we knew better, security dialogs used to rely on this sort of constantly interruptive modal nagging. This led to a distinct lack of security as most people grew into the habit of accepting pretty much any dialog that was thrown at them just so that they could get to doing what they had set out to do.

We need to keep this type of consent dialog rare so that consent may remain meaningful and not something that people sleepwalk their way into accepting. We need it for sites that process genetic information, for situations in which health information may get shared, for ethnographic studies that may cover sensitive topics, for when an invasive procedure such as a credit check is involved.

In the same way that the smoking industry chose to write its health warnings in all-caps because of studies showing that people read capitalised text less, beyond a certain threshold increased reliance on consent endangers users rather than protecting them.

It may be unintentionally. It may be through lack of consideration. I neither wish nor need to assume malice. But that is exactly what the advertising industry is planning to do.

The idea that informed consent can be obtained for the byzantine processing of personal data carried out in the advertising world is rooted in the foolish notion that a reasonably short piece of text can inform anyone as to how extensive the profiling is, as to how many hundreds of companies get to see your behavioural data, as to the risks you would be — supposedly willingly — consenting to. Short of a week-long course in information theory, data protection, auctions and real-time bidding, and a full overview of the mind-boggling complexity of the advertising ecosystem the idea of prior informed consent is a joke. Much of the time, these companies don't even understand the implications of their own data collection. Trying to lure users into it is actively disingenuous. Trying to force sites that rely on advertising revenue into using the trust relationship they have with their readers to obtain that consent borders on malicious. Publishers find themselves in a Hunger Games scenario in which short of an outright uprising they have to either play by rules that sicken them or face certain death.

Where does that leave us?

Details of the discussion get technical, but the short of it is simple: the advertising industry could respond to the new GDPR regulations by toning down the invasiveness of its personal data practices; instead, it is attempting to force publishers to take responsibility for getting their users to sign their personal data over.

It may seem rashly idealistic to believe that advertising actually could rely much less on tracking but it is not as if they really have much of a choice. Regulation or not, now that Safari has brilliantly demonstrated that it is possible to get rid of third-party tracking without breaking the Web it is only a matter of time before other browsers will have to stop being complicit in violating the privacy of their users. Sure enough tracking companies are desperately attempting to fight back with nasty hacks, but those are just the agonising throes of a dying breed. It's over. Much remains to be done but the tide has turned. It is time to focus on ways other than tracking to get an edge in advertising. Companies that are already investing in next generation techniques will prevail, those that fight a rearguard battle against their own fate will get steamrolled into oblivion.

Like a dying beast, the trackers do not care what they take down with them. You can see this in IAB Europe's consent framework, no doubt will you see it even more forcefully from individual advertising networks — probably through announcements made as close to the GDPR deadline as possible so as to force publishers into hasty decisions.

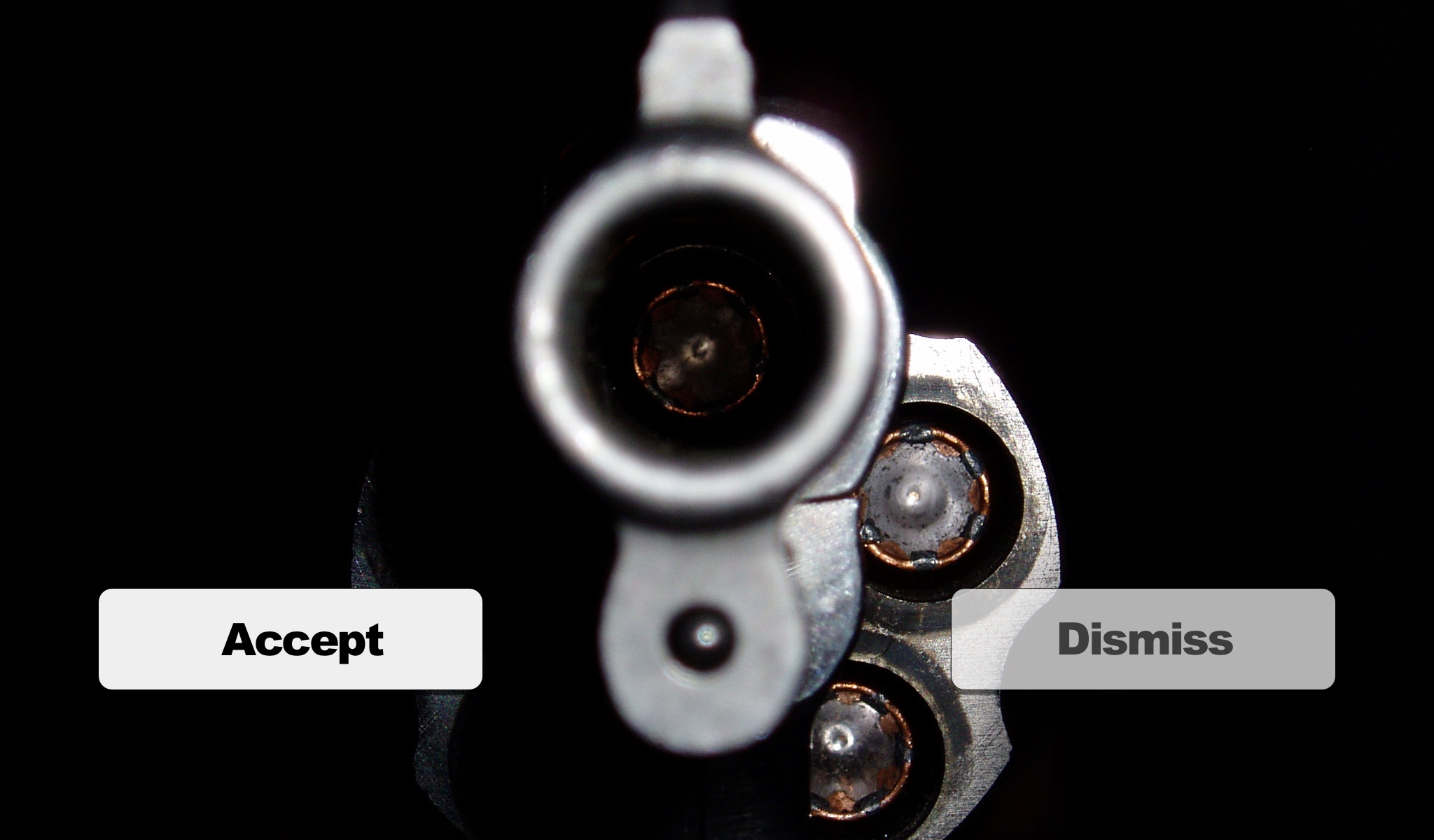

It falls upon us all to keep them from rendering consent unusable when it is really needed. In Europe, it's likely that you're going to start seeing much more modal, intrusive consent dialogs when visiting a site. Don't blame the publishers, they're acting at gunpoint and facing a cartel. But know this: nothing forces you to consent. They are not allowed to lock you out if you refuse. There's only one thing you need to do: Just Click No.