The Trouble With Troggles.

Privacy as Product

In 1765 the British Parliament, needing money to pay the British troops stationed in America to protect the colonies from the ever-perfidious French, passed the Stamp Act. The Act imposed heavy direct taxes on a variety of printed materials in the British colonies, including in British America. Among many other provisions was a tax on advertising: “For every advertisement to be contained in any gazette, news paper, or other paper, or any pamphlet which shall be so printed, a duty of two shillings.” The Act proved popular enough to elicit riots that saw tax collectors hanged in effigy when they weren’t tarred and feathered, and it remains famous to this day for the slogan it inspired: “No taxation without representation.” It was repealed the following year.

Ok — but what does this have to do with privacy? A tax on advertising is what.

In today’s digital world, two and a half centuries later, ads are again heavily taxed. To begin with, there is the well-known “adtech tax” in which advertising intermediaries help themselves to more than half of each ad impression’s direct worth in a system so opaque that we can’t even account for 15% of the money.

Evidently, that’s a problem of market power. But this market power didn’t wish itself into existence out of thin air like a stubborn ghost of the damned. The digital world is, in a very literal sense, made of flows of information and it is shaped by the rules that dictate how information can flow. The rules we have today explicitly make third parties much more powerful than first parties because they are allowed to recognise people over a much, much larger surface. This point is one that I have seen many fail to fully grasp simply because it seems so absurd that things would work this way so please bear with me as I belabour it: this one rule of information flows that allows third parties to identify people across contexts is on its own enough to grant them enough power to levy excessive prices in exchange for abysmal accountability.

More important than the adtech tax, and much harder to measure, is the data tax. Most advertising intermediaries don’t just use the data that they collect in any given interaction in order to deliver a service to that specific publisher. They reuse the data from that publisher’s site in order to make their own independent money elsewhere. For instance, an ad intermediary servicing the (imaginary) NoVaxxTruthers site can recognise a person who earlier that same day had been checking out, say, high-end soundbars on Wirecutter. The hard work of developing the content and experience that attract a loyal high-end audio intender audience is all carried out by The Wirecutter, but a very real chunk of that investment is being redirected to support the NoVaxxTruthers disinfo content farm — as well as the ad intermediary making money off every transaction. My example is fictitious but the problem is everything but: just follow Check My Ads for an endless stream of examples of how stalwart brand names of the disinformation economy like Google or Criteo keep engaging in this behaviour. TL;DR: Digital advertising, as it exists today, is first and foremost a tax on high-quality sites that is used to subsidise low-quality content, including bottom-of-the-barrel hate and disinfo sites, while enriching intermediaries.

Designing rules to govern flows of information so as to achieve specific outcomes (or at least to prevent some particularly bad problems) is the domain of data governance. When the data is about people or could affect people, that’s the domain of the subset of data governance known as privacy. If our goals is to reward quality publishers for the work they put into developing worthy content, beneficial services, and a loyal audience while putting a stop to the systemic subsidy of toxic content — the disingenuously-called “business model of the Open Web” — we need to get these rules right. For instance, much of what the “Privacy Sandbox” does is to remove identifiability while preserving the actions that identifiability supports today. This not only arguably changes nothing under the GDPR but also serves to preserve a system that harms much more than it helps. We can, and we must, do better.

You would think that anyone running a legitimate consumer-facing business with quality content and a loyal audience would be up in arms about this, and that they would all be working hard to define alternative rules throught both through tech and law. Why would anyone want to subsidise their cheap and toxic competitors? And it’s not as if this were particularly hard to legislate: we can simply outlaw (ideally using both tech and regulation) the reuse of data by third parties outside of a very narrow set of purpose-limited exemptions (banning the sale of data, in CPRA terms, or third-party data controllers, for the GDPR folks).

You would think that. But you’d be wrong.

Must The Show Go On?

If you start to reach out to businesses about this, more often than not you will encounter people whose job seems to involve zealously defending their employer’s right to keep digging its own grave by sticking to a system that’s plundering its assets. They want as much taxation as possible with as little representation as can be had for the money. You would expect such positions from a data broker. You might even expect publishers to want to maintain the system in the very short term as they map out a transition. But actively defending your right to give away your audience data to competitors isn’t good business — in fact, it’s economically irrational. So why insist on it?

The problem is with who we’ve put in charge of privacy concerns and how we’ve organised privacy in businesses. Those who’ve read Ari Ezra Waldman’s excellent book Industry Unbound (or his recent equally-excellent article Privacy, Practice, and Performance) won’t be surprised to hear that the job of many “privacy pros” doesn’t involve doing much about privacy or that the rights/compliance model of privacy is mostly about vacuous rituals. However, given the size of the economic incentives at stake, it might still be surprising that it stays that way.

Most companies, including digitally native ones, have an underdeveloped and unsophisticated approach to privacy and data governance. This isn’t just an issue of compliance departments — if you try asking a senior digital leader “what are you trying to achieve with your privacy strategy?” very few will produce a cogent answer. For the most part you’ll hear “we’re just trying to stay out of trouble.” Oh, and “we take your privacy very seriously.”

I know that this will feel unfair to some of you, but this calls for candour. From the deepest trenches all the way up to the Board and across every branch of business from tech to marketing and data to B2B, the perception that people have of privacy compliance work is that it is perfunctory, pro forma, and useless. It feels fake, often because it is. People go along with it because it’s protected by the Don’t Feed The Lawyers mystique. No one wants to touch that kind of privacy work for fear that it will suck out all of your life force until you look like cheap CGI beef jerky. You stand aside, you say nothing and nod even though it’s obvious they can’t tell a cookie from a database pipeline, you smile, you let them do their pointless dance of inventory and consent, you pray it’s short, and finally you let out a breath and get back to real productive work. That’s the reality of how teams across the digital landscape interact with their privacy colleagues.

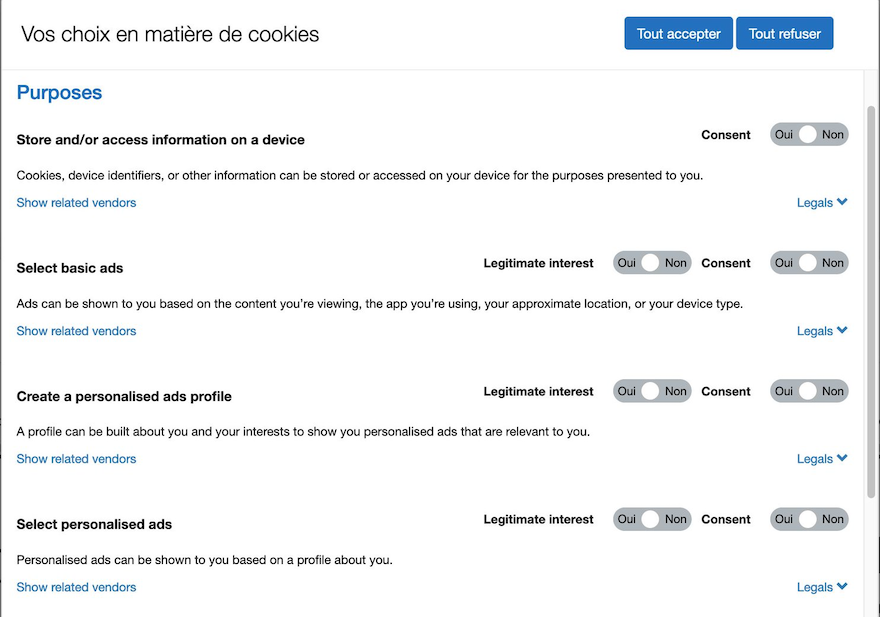

And when the time comes that regulators invite input into data regulation, the same aloof priesthood who carry out this ceremonial compliance are sent to explain exactly what brand of toothless bureaucracy they like best. Like, you know, we’re bleeding data, handing over core company assets to competitor, and our users hate us with fiery rage, but let’s do troggles.

This isn’t a great system. The problem we’re facing is simple: privacy is a product issue, but it’s predominantly being treated as a compliance problem.

Assembling a privacy team for their compliance know-how is like picking a restaurant chef based on their expertise as a hygiene inspector. I mean, hey, it’ll come in handy at times. Your restaurant will almost certainly stay out of trouble with the authorities, so there’s that. And some hygiene inspectors are good cooks! You might get lucky. You might!

This is not to say that compliance isn’t required: it absolutely is. Compliance work has various degrees of relevance across all product work, and data compliance should be an important stakeholder for a privacy team. You’re not putting your marketing compliance colleague in charge of all creative copy, are you? Because if you are I’ve got a restaurant recommendation for you.

Most people in digital businesses understand at some level that that’s not right. But the field has been so monopolised by bad performative solutions we often lack the words to formulate the problem, let alone find a path to the solution.

You Want To Break Free

It really doesn’t have to be this way. I don’t claim to have a magic methodology to make this work for everyone, but here’s a starting place: to succeed in the digital space you need to be deliberate about the rules that govern flows of information, which means that you need to have a deliberate privacy strategy, and in most cases compliance is only going to be a fraction of that strategy. (It might not even be part of the strategy and only managed as an operational concern.)

If you’re a data broker or a content farm, your strategy might very well be to gather as much data or broadcast as much data as possible with no respect for the people who are impacted. That’s ugly, but at least it’s coherent. If you’re operating any kind of consumer-facing property that needs to retain the trust of your users and that makes money by understanding a loyal audience (typically with advertising), you’re likely to want some kind of Vegas Rule in which what happens on your site stays there. It’s likely you won’t be able to get there right away, but you can start mapping out the steps. That’s what a strategy is, and it’s a lot better than hoping someone can go drown your problems under the privacy policy.

How you staff that work will depend on your business. You want someone who understands the strategic and economic value of your audience, and gets the ways in which giving data away to others undermines it. They’ll have to be conversant with your operational practices and with how changing the ways in which data flows across your business (all of your business — tech, data, advertising, marketing…) will impact your operations for good and for bad. You want to focus on iterative long-term improvements rather than short-term revenue — maybe don’t give this to your 24-year-old head of programmatic yield who just wants good numbers so they can get a better job with your competitor. The ability to translate between lawyers and others, and a lack of automatic deference to unsubstantiated legal opinion (and skepticism in the face of outside counsel, it’s usually justified) are core requirements. Ideally, this person should be able to understand how to make a case in technical or policy venues.

I tend to think first and foremost of product people for this kind of work because they are able to have a cross-functional understanding of the business and a visceral sense of what is best for your users — but of course, you may have different local preferences. You definitely want someone in charge who sees a proposal to use troggles and doesn’t need to know that it’s not compliant — perhaps not even in Ireland — to reject it as and with a joke.

There are interesting and difficult problems in privacy law, but the overwhelming majority of privacy problems that a website or app will face are not legal problems: they're operational, product design, or revenue problems. You need a good legal partner who gets how operators work but you need your focus to be on the pain points, not on compliance theatre.

You might have noticed that I’ve written an entire post about privacy while saying almost nothing about how people are affected by this bountiful data sharing. Evidently I do believe that that matters (a lot) but others have written about it better than I would, and you don’t need to agree with that to heed my point. If you’re in any kind of position of leadership or influence at your company, just know that you don’t have to put up with the nonsensical rigmarole of pretense privacy compliance. Privacy is a strategic product concern that is key to digital businesses and should be treated as such, not a nuisance to be lawyered away with wobbly incantations.