Composting the Oligarchy to Regrow Organizations

Transmutations

This piece was initially written as part of the "OSS Growing Pains Workshop" which was convened in March 2024 by Joshua Tan, Mako Hill, Seth Frey, and yours truly at Princeton CITP. The workshop was highly stimulating and resulted in the publication of a zine produced by Adina Glickstein, Drew Hornbein, and Nathan Schneider. I highly recommend that you download (and print!) the zine as it's a work of great beauty. You can read this same piece there in its intended presentation. I am deeply thankful to everyone who was involved in both the workshop and the zine.

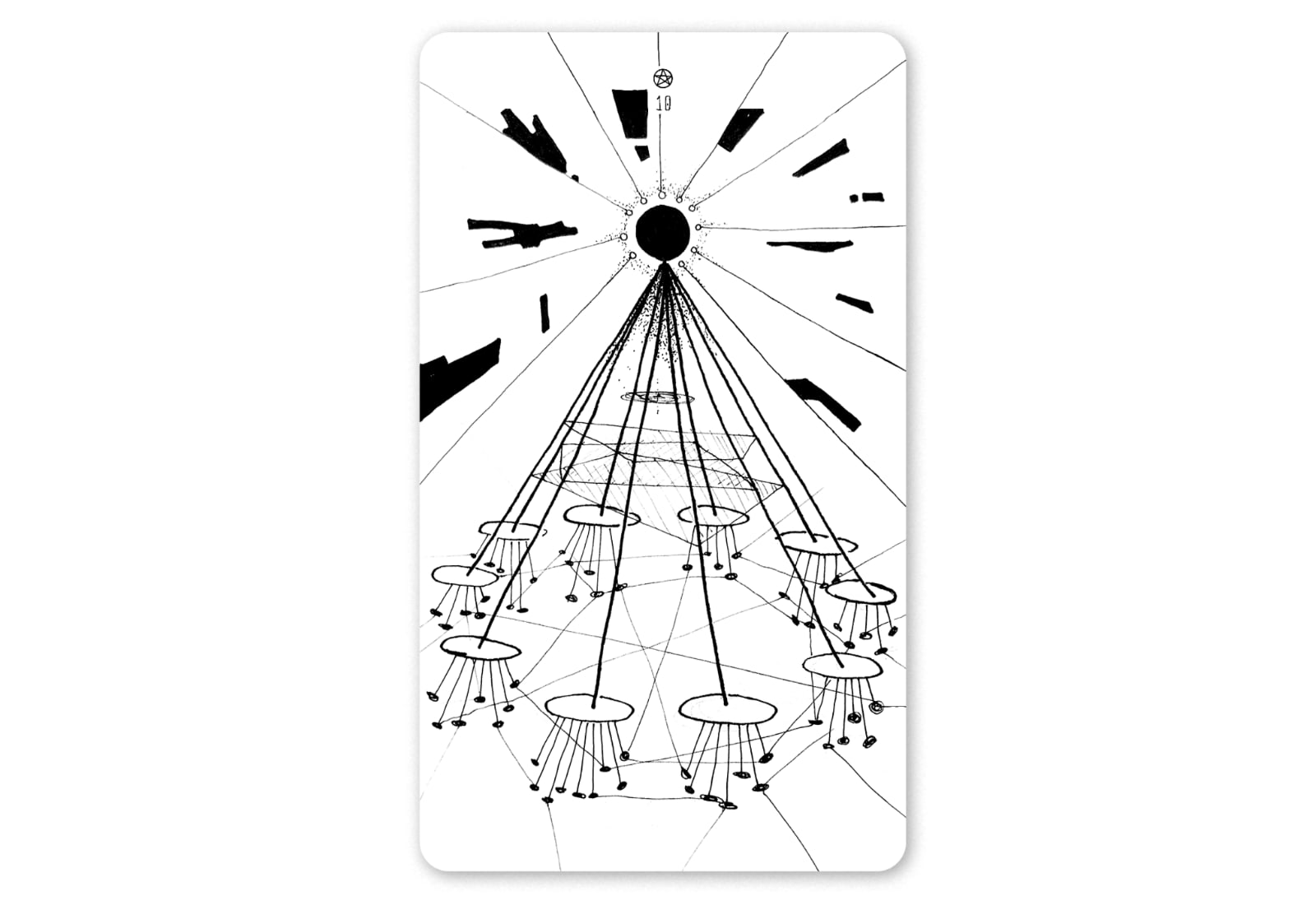

The illustration above, as well as the gorgeous art in the zine, were made by Drew Hornbein at Ritual Point Studio. Many thanks to Drew for letting me use it.

This post's date reflects the time at which it was written, even though it was published later to align with the zine. Unusually, this text follows US spelling conventions to align with the published version.

Peer production projects may be birthed from ideals of equality but they don’t grow up that way. After an initial phase of open, egalitarian participation, quantitative evidence concerning the evolution of peer production communities over time indicates that — irrespective of their stated values — they transition to a second phase as oligarchies.1

This presents a challenge for the long-term sustainability of these organizations and projects: on the one hand, the oversight and institutional expertise of the oligarchy provides an important ecosystem service in protecting the quality of a peer-produced good when it becomes valuable enough to attract subversion. On the other, as time passes the oligarchy invariably becomes increasingly disconnected from the real-world problems that are relevant to its constituency and decreasingly equipped to handle the issues that face the organization as the world changes. As a result, the organization progressively loses relevance.

This process of calcification can be understood in terms of institutional evolution.2 According to Allen, Farrell, and Shalizi “an institution exists when the individual members of a community have institutional beliefs that are similar enough that they are roughly self-reproducing and mutually reinforcing over most situations most of the time.” Within this epistemic understanding of institutions, institutional arrangements change when novel beliefs about the rules in use spread across the network of participants in an organization. But such participant networks are not typically egalitarian as some nodes will be far more connected (in technical terms, they will have a higher degree) than others. Intuitively, members of the elite are in contact with more participants than others, and this affects how new ideas — and therefore novel institutions with a different power distribution — may spread: “power asymmetries combined with different attitudes among powerful actors towards specific institutional beliefs may mean that beliefs that sit poorly with power elites are less likely to spread contagiously across the network.” If highly connected participants refuse to spread new beliefs, that will structurally slow them down.

As the organization solidifies around a set of institutional beliefs and develops the means to keep challenges from new ideas at bay, we can expect its epistemic diversity to drop even if new participants keep joining. Those whose ideas differ too much from the established norms will find it impossible to thrive and leave. Given that epistemic diversity is a key component of resilience,3 we can expect the organization to become increasingly brittle.

In some cases, at this stage, it may be best to simply compost the organization itself and let it be replaced by a newer, better alternative that will serve its purpose until it too succumbs to the corrosion of oligarchy. But some of these organizations represent important Schelling points: we benefit greatly from having just the one Wikipedia and in some domains such as standards organizations we would struggle if we had more than one (or at worst a handful) of options.4 This means not only that replacing these organizations is costly, but also that, due to the cost of replacing them, they are likely to persist and to keep occupying their niche far past the point of elite capture.

Should we give up, form a doom cult around the Iron Law of Oligarchy and travel the world chanting “who says organization, says oligarchy”5 or can we map a path to a third phase of peer production organizations that can follow elite capture? Is it possible to eliminate the oligarchy while maintaining the processes they drive that protect the value of the public good that the organization produces?

It seems unlikely that there would be a universal method to transmute the governance of a peer production organization out of its oligarchic phase, but there is some guidance that should help an institutional insurrectionist devise a course of action.

First, in order to obsolete the oligarchy, it is important to encode valuable work that it provides in an institutional process that can operate without them. Presumably, the oligarchy arose because some form of gatekeeping or of quality assurance became (and likely remains) necessary. Capturing the useful component of their contribution is challenging because it requires extracting the governing methods that sustain the produced common good’s quality while eliminating the oligarchy’s idiosyncracies.

In many way, the oligarchs will be the repositories of much of the knowledge required to support peer production but asking them to create institutions is more likely to capture their pet peeves than to produce an effective governance arrangement. One defining feature of entrenched oligarchy is a propensity to dedicate unhealthy amounts of energy to debating largely insignificant changes to process in a behavior reminiscent of the more creative parts of the CIA’s Simple Sabotage Field Manual.6 One path to success may be to focus clearly on what exactly it is that the organization produces and what the best way is to safeguard the quality of that production. Ideally, that will be a minimal, trimmed down process that can readily be understood by the community, including newcomers. It is key that it be designed without any of the oligarchy’s baggage, none of the fear, complexity, or peeves that haunt them. This may require providing them with an institutional arena in which to work on their gripes, as a retirement home of sorts.

Second, you want to create pathways for minoritarian voice. This is valuable in any organization, but under the epistemic understanding of institutions spreading new ideas that the elite is inimical to will be a driver of change. One approach may be to create safe spaces for incubation while ensuring that incubated ideas are given high, intensional visibility to participants. This should reintroduce viewpoint diversity, helping make the organization more resilient as it transitions away from its entrenched leadership.

Third, it can be helpful to develop a historical view, and in this the oligarchy can even be put to good use as it holds the required knowledge. History gives depth to the rules in play, and notably explains the context in which they arose and why they were useful when they were put in place. In turn, this makes them easier to critique by pointing out how the context has changed. You want cultural transmission that is dense enough that you can engage with it and make it yours rather than a pronouncement from the heavens.

Fourth, create direct contact between non-elite participants. We can capture the elite blockade by “assuming that if nodes of high degree belong disproportionately to a particular class which is inimical to a new belief, and so resist its spread, the new belief is being propagated over a network from which the high-degree nodes have been preferentially removed.”2 The theory here is that if elite power is encoded in a social network, you can change that by changing the network — an intervention that may prove practical in relatively small communities. Creating opportunities for non-oligarchic coordination (or even simply contact) may be enough to build the right bridges. Generally, networks in which elite actors are less dominant (i.e. in which there are smaller differences in node degrees) are less susceptible to elite blockade.

And, finally, don’t forget to eliminate the oligarchy. This is a political problem, especially if you hope to achieve it faster than one funeral at a time. It is unlikely that oligarchs will step down of their own free will because each and everyone believes themselves impervious to becoming detached from reality in the same way that most drivers believe themselves to drive better than the average. If you’re a newer participant, build coalitions, run in elections even you may have to do so more than once in order to win. If you’re an enlightened oligarch, mentor and cultivate newcomers — and step the fuck down.

If you succeed you will have a new generation of leaders — you need new leaders — and it’s likely that, eventually, a new oligarchy will rise. You can delay it by paying attention to the creation of strong democratic processes and the fiercely egalitarian culture that supports it. But what matters is that you’ve at least kicked the can down the road and made your peer production organization sustainable for another cycle, transmuting the iron law of oligarchy into dirt from which to grow resilient futures.