Transnational Digital Public Infrastructure, Tech Governance, and Industrial Policy

The Public Interest Internet

Disclaimer: more so than usual, this post is several months' worth of notes very roughly straightened out and assembled. I could (and will) keep picking at this problem for months more but given fast-increasing interest in this topic, I feel it's best to open up. Feedback very welcome!

Allow me to open with a wildly speculative question: What if the internet were public interest technology? I mean "internet" the way most people understand it, which is to say our whole digital sphere, and by "public interest" I don't mean tinkering at the margins to reduce harm from some bad actors or painting some glossy ethics principles atop a pile of exploitative rent-seeking — I mean through and through, warts and all, an internet that works in support of a credible, pragmatic definition of the common good.1

Is that too wildly speculative? I think not. I am not talking about a utopian project here — a public interest internet would be a glorious imperfect mess and it would be far from problem-free. But while there is a lot of solid thinking about various digital issues or pieces of internet infrastructure (much of which I rely upon here), including a great blog series from Danny O'Brien and friends, I have yet to read to an answer to this question: What global digital architecture should we assemble if we take seriously the idea that the internet should be public interest technology?

I can only cover so much in the space of a single piece, but in order to sketch the shape of this architecture I will look at:

- what we should consider to be digital infrastructure and the consequences of its capture;

- the problems with our current approach to internet standards;

- limits to the main approach to digital regulation that states are deploying;

- what problems exist with industrial policy and territorial state investment in the context of a transnational commons;

- how to approach the governance of transnational public infrastructure in a manner that is (by necessity) democratic but that limits encroachment on state sovereignty (and in fact improves the situation compared to the big tech status quo);

- how to pay for this; and

- precedent and proposals showing that this architecture is pragmatic, implementable, and doesn't need to reinvent the wheel.

Working out the above in full detail is a research programme in its own right (and many of the parts benefit from existing high quality work) but what I hope to do here is to show how this all fits together as a coherent whole.

Hope in the Dead of Night

I am not embarking on this project out of pure academic curiosity. There is an early but growing sense of optimism that we may have seen the worst of the big technocracies' rule over our digital lives and might be approaching a turning point. (A trend that includes the recent We Need To Rewild The Internet from Maria Farrell and yours truly.) If we have a shot at shaping a liberated internet, we need to be prepared with what we want. What is it that we're fixing and what is the fix?

It's natural to complain first and foremost about the more high-level, user-facing issues — for example that people are mean on social media, that search results are useless, or that journalism is dying — but our troubles start with infrastructure, with who controls it, and with how they use that control to shape what is and isn't possible on the internet. We have ways to improve content moderation and promising new products to go with, we know that search didn't need to be bad (though Google's approach would get there no matter what) and we can fix it, and once you remove the tens of percent of baseless taxation from advertising and app store infrastructure providers, as well as the free labour extracted from search and social infrastructure companies, journalism is a perfectly viable business to be in. We are not living in that world because the companies that operate our digital infrastructure have decided that they don't want us to be living in that world — and no antitrust action to date has seriously dispersed that power.

Our goal is therefore to recapture digital infrastructure in the public interest.

A Problem With Authority

Recapture from whom? Isn't that famous monopoly on violence is the only real source of power? Authority is not the sole remit of the state and we can define it precisely enough for our needs. Already twenty years ago Jim Whitman pointed out that "the starting point for nearly all global governance perspectives is a recognition that power, authority and the capacity to affect significant outcomes is no longer the exclusive preserve of states."2

In fact, Gráinne de Búrca has made this very point with respect to transnational fora such as internet standards organisations (in which larger tech companies holds inordinate power, as I will cover farther down): "While it is true that the state holds a monopoly of coercive authority, with the capacity to compel obedience backed by force, it does not mean that the exercise of other forms of public power is not authoritative. There are a number of ways in which decisions made in transnational fora become authoritative, in the sense of having the power to determine outcomes and to compel obedience."3 She notably mentions both the Codex Alimentarius and the Basel Committee, two "voluntary" standards that are de facto authoritative. And indeed, we can simply say that "authority over social or economic relations is exercised whenever the choices open to others are changed."4

For our purposes, we can therefore use this definition: infrastructural authority describes an actor's capacity to change the choices open to others by using its control over a specific piece of infrastructure.

Captured Infrastructure

What counts as infrastructure in this context? The digital sphere is large and complex, and many different types of activities take place there. We shouldn't be surprised to discover that a listing of digital infrastructure is long. Many scholars and policymakers approach the question with a restrictive understanding of what counts as infrastructure, but if we are to have a comprehensive approach to the problem, I believe that that's a mistake:

- Some only consider internet infrastructure to be relatively low-level components such as cables, IP addresses, BGP, or DNS. That is needlessly reductive and there is no reason other than historical to make that cut. Search, browsers, advertising, standards, secure chat, open source stacks, social media are just as infrastructural to people's lives.

- Others only consider payment, identity, and data provision as being eligible for digital public infrastructure. But society needs a lot more. And, more to the point, if you only have those three items under democratic control but the rest of digital infrastructure isn't, public life will be just as captured.

Like others, I prefer Brett Frischmann's capacious definition of infrastructure as "shared means to many ends."5 It is conceptually simple and captures the intuitive understanding that there are systems which we use collectively for many different things. This implies, also intuitively, that significant trouble happens when such systems break. Because infrastructure enables many outcomes, it empowers us to pursue a great multiplicity of human ends. As Debbie Chachra put it, we can consider "infrastructure as agency"6 and further that "infrastructure is care at scale."7

This link between infrastructure and agency is double-edged, however. When an actor uses its infrastructural authority to further its own needs and to control the choices made by its users — to limit and control their agency — we speak of captured infrastructure. As I wrote in Capture Resistance, "capture happens when an attacker is able to observe or control your operations, or to extract rent from them, and the accumulation of capture adds up to centralisation."

That's the situation we are dealing with on the internet today: essential digital infrastructure is captured by private companies. Whoever controls infrastructure shapes what is possible — often at generational time scales. This puts them in a position to observe and nudge activity at massive scale, to limit options, to front-run and arbitrage exchanges. It is, all told, a stupendous level of power over all digitalised aspects of society.

Such power needs to be overseen by the people it affects. This is true of any infrastructure, but it's particularly true of the internet which is becoming “the infrastructure of all infrastructure.”8 And in addition to the authoritarian impacts of captured infrastructure, as I will note below, there are reasons to believe that no complex system can be managed competently and sustainably without democratic control. (Note that privately operated infrastructure can be fine if it is publicly governed, but that is not the world we have built so far.)

Example Capture

This may seem abstract and up to a point arbitrary. So let's look at a real-world example of the effects of captured infrastructure, focusing on a domain that few people think of as being infrastructural to begin with, but the failings of which have important societal consequences — the kind of consequence you would expect a public interest system to prevent. I'm talking about digital advertising.

Almost everyone hates advertising, and digital advertising even more so. However, advertising has (nominally at least) a public interest aspect: it subsidises access to services. That's the only reason it hasn't been banned outright. Of course, we all know that adtech and big tech execs use this promise of public interest as a fig leaf to justify indefensible data and business practices. But this leads to the question: in what ways does the capture of advertising infrastructure hurt society, and what would it look like if we organised digital advertising in the public interest? What is, and you might want to sit down for this question, public interest adtech?

The basic idea of advertising is simple. Some companies are willing to pay to put information in front of people to whom they don't have access. Other entities offer services that draw crowds, and sell advertising space to the first group, which helps finance their operation. Typically, specific services will be more attractive to specific audiences, which that service provider gets to know better from working to figure out what their users, readers, watchers, etc. want. There are therefore three constituencies involved in advertising:

- Advertisers, who put money into the system.

- Publishers, understood broadly as any service that offers ad space, whose offerings are subsidised (often in their entirety) by ads.

- People, who can benefit from accessing services at lower prices and whose attention is interfered with by advertising.

This system is infrastructural because we have shared means — ad networks that arbitrary publishers can just tap into — that support many ends — a huge variety of publishers, an even wider diversity of advertised products, and the many interests of people who access subsidised systems. Much as advertising may be disliked, if you were to remove it overnight huge parts of the internet (and not just the internet) would simply collapse.

Public interest advertising infrastructure wouldn't be a panacea, but we can sketch out what it would look like. Advertisers would be getting reasonably effective ads at reasonable prices, and perhaps more importantly they would have credible visibility into how their campaigns are performing. Publishers would be supported, we would see much less reliance on paywalls and subscriptions, a significant part of which would go to supporting quality journalism that holds power to account. And people wouldn't have their every behaviour tracked across the internet nor would they be exposed to ugly, overwhelming, resource-draining ads, but would be able to access much content and services with only rare paywalls. Not a utopian option, but arguably an acceptable compromise.

How far is this from today's situation? Very far. The fact of the matter is that all three of those constituencies are suffering from a system that is good for none of them. Why? Because our advertising infrastructure has been captured by infrastructure providers instead of being controlled by the constituencies it is supposed to serve.

Advertisers are losing out because there is scant evidence that they are actually converting sales and (for more from those dangerous socialists at the Harvard Business Review) signs that marketers highly overestimate digital advertising effectiveness. That's when the ad platforms don't flat out lie while grading their own homework: "But even when that salesperson and customer have met in person, exchanged multiple emails and talked on the phone, walled garden platforms, namely Google and Meta, often manage to claim those sales as driven by ad campaigns on their platforms." And when advertisers are being fleeced out of their money, they pass on the added cost to consumers.

Publishers are losing out because they're not making enough money, despite constantly increasing ad pressure. As designed, our ad infrastructure creates a system in which high quality publishers, who work to produce contexts in which advertising has a high value, are subsidising bottom-of-the-barrel ones because, due to the deliberate lack of privacy of the system, people can be identified in high quality contexts and targeted more cheaply and repeatedly in low quality ones. This has led to the emergence of made-for-advertising sites (MFA) that syphon off traffic and the business model of which is solely to benefit from this subsidy effect in exchange for no social value. Advertisers would predominantly prefer to reach people in high quality contexts, too, but they are being lied to about the attribution of their ad views. Needless to say, this arrangement benefits those who intermediate these exchanges and can choose how ad impressions are arbitraged. The system works even better if you own a browser that offers no protection from third-party cookies, a mobile operating system that defaults to exposing persistent identifiers, and a search engine with which you can direct traffic to low-quality sites.

And, finally, people are losing out because their data is being shuttled around in one massive continuous breach of privacy, they get worse publisher options as the high quality ones progressively cut costs and die off, and a far worse ad experience than could be justified as a trade-off for access. It's no surprise that ad blocking keeps growing, further leading the system towards a state of total disrepair.

A competitive market could serve as a check on the power of ad intermediaries, but the (deliberate) opacity of the system coupled with the concentration of the market render that impossible. But markets are only one kind of institution amongst many options that offer checks and balances. Our advertising infrastructure only works the way it does because we've decided to let it work that way, because we've allowed the infrastructure providers to make it work exclusively for their own benefit, just tossing over enough crumbs to have media CEOs back them up. How we run infrastructure determines how we run society, and that decision belongs to us all.

The Opposite of Capture: Infrastructure Neutrality

No technology is neutral, and infrastructure has politics more so even than other artefacts. But there is a specific sense in which infrastructure can be described as neutral when infrastructural authority is appropriately contained. It has two components:

- First, recognising that there is a fundamental conflict between the self-interest of the infrastructure owner and social welfare (since the former can always decide to extract rent against the latter), we must ensure that the unavoidable bias in infrastructural choices is controlled by the infrastructure's users.

- And second, the intelligence that can be gathered by operating the infrastructure must not be used to shape how the infrastructure operates without a direct, debated political decision by its stakeholders.

The latter point is less readily obvious. If you can dynamically use data as the system operates in order to optimise its behaviour, how can that be bad? The problem lies in the "many uses" part of the value of infrastructure. By optimising for what we know, we foreclose what we don't. Infrastructure is about happy accidents; there are no happy accidents in optimised systems.9 Infrastructure is fundamental to society and society needs to remain open, flexible, free, with opportunities and options. "Optimization entails opportunity costs of the sort often associated with path dependency."5 Infrastructure that is dynamically optimised (in ways that are not strictly limited and under direct political control of its users) will create a persistent gradient of power and lock its users into a specific set of trajectories.

Another way to think about it is that the only way that data gathered while operating infrastructure can be applied to shape that infrastructure is to optimise it, and optimisation is fundamentally incompatible with infrastructure. As Mandy Brown puts it, "Optimization presumes a kind of certainty about the circumstances one is optimizing for, but that certainty is, more often than not, illusory." She goes on to cite Deb Chachra:

Making systems resilient is fundamentally at odds with optimization, because optimizing a system means taking out any slack. A truly optimized, and thus efficient, system is only possible with near-perfect knowledge about the system, together with the ability to observe and implement a response. For a system to be reliable, on the other hand, there have to be some unused resources to draw on when the unexpected happens, which, well, happens predictably. 6

This creates two intimately related problems (that show just how tightly related infrastructure and democracy are). First, that optimised infrastructure cannot be resilient because it lacks response diversity in how it operates (the slack that Chachra mentions). Response diversity is the property of a system or population such that it has a range of potential answers in the face of perturbation, and that range is what enables the system to overcome shocks. That's key to resilience. And second, optimised infrastructure assumes that you know better than your users what's good for them (anyone who's had to interact with big tech people on such topics will know how real that is), which means that you will constrain or counteract their preferred behaviour. This is problematic from an epistemic democracy perspective — you will get a less effective democracy for it — and it further hurts resilience by limiting response diversity at higher layers as well.

Infrastructure neutrality is very similar to the end-to-end principle since captured infrastructure seeks to optimise at the intermediary level — which violates this principle notably by making change and novelty much harder, and the overall system less reliable and secure.

But just as the end-to-end principle isn't absolute but only a starting point from which to debate what can be acceptably optimised, infrastructure neutrality is not an absolute interdiction against learning from infrastructure operations or optimising if done well: that is what the requirement on political decision-making provides. Requiring a political decision means that it's possible to learn from operations, but that the lessons have to be passed through the crucible of debate, which serves to reduce the OKR-driven stupidity of middle management optimisation and helps keep the system open to change, to a plurality of needs and ways of thinking.

When it comes to today's internet, however, we have failed to impose infrastructure neutrality across almost all of the board.

The Vicious Cycle of Data Commodities

I picked advertising as an example above in part to show that a public interest internet can be conceived of in domains that people have given up on, but also to make a point about infrastructure and the surveillance business model that dominates the internet.

The surveillance advertising, often simply described as "the business model of the internet", has been much maligned and for good reason. But when critics blame it for the many ills of the internet, I think that they are missing the forest for the trees. The problem goes deeper.

It is not just personal data that is made into a commodity — it is all information. We can see this at play with the current wave of generative AI, but it was already true in the previous iterations of that same trend as current AI search products, for instance search snippets, AMP, news aggregators, or voice assistants that answer questions without attributing the source.

By making all information as legible as possible across as much of the digital sphere as they can, digital infrastructure providers create opportunities for optimisation. And each such opportunity for optimisation is a chance for them to arbitrage information differentials between different participants, and therefore to shape the system to their advantage, to increase the rent they collect, to control the choices that other actors may make.

Surveillance advertising is part of that system but it does not define its essence. The logic of the system is a vicious cycle:

- Use control over infrastructure to force information in the digital sphere to be more legible: sites that share more user behaviour are granted higher CPMs, publishers who provide more reusable formats like schema.org or AMP are ranked higher, vendors who create a brand page on your commerce platform see more buyers sent their way, etc.

- Use that legibility to optimise the infrastructure in a way that drives greater profit. The opportunities abound: markets are information animals, but things like the price system and quality signals are comparatively slow and low bandwidth. This legibility enables the infrastructure operator to structurally front-run all the markets that rely on it.

- Use the profits to buy more infrastructure and consolidate more of the stack, deeper. Return to 1.

Surveillance capitalism is but a subset of the issue. Addressing it comprehensively can only be done at the infrastructural level. The good news is that there are ways of governing our infrastructure better — and they also make the business of surveillance a lot less attractive.

Where Are Your Standards Now?

Speaking of markets and privacy, I appreciate the CMA's efforts in handling the "Privacy Sandbox" case as essentially a standards organisation of last resort.10 But I don't believe that the CMA has the industrial policy mandate to guide the public interest changes that our adtech infrastructure needs, as opposed to supporting a mildly reformist maintenance of the status quo. And the process includes no forcing function to get Google to stop producing underwhelming proposals and thereby to keep slow-walking the phase-out of third-party cookies — now seven+ years behind the rest of the industry and counting. (The trajectory of Chrome with respect to privacy is, in fact, very similar to that followed by Facebook as described by Dina Srinivasan.)

Why does the CMA have to step into a standards process and why are the existing bodies in charge of internet governance, largely through standards-making, falling so far short of the mark?

The situation varies between technical domains and SDOs, but the overall problem remains largely the same. I will focus on the web and the W3C as an example since that is what I know best. The general issue is that our internet governance systems are woefully unequal to the task of governing criticial infrastructure — even if we only consider standards — for five billion people. A recent UN Human Rights Council report captures the heart of the problem:

Technical standards are typically adopted by consensus and compliance is usually voluntary. Standards nevertheless regularize and constrain behaviour (regulative function) because they provide the authoritative guidance necessary to participate competitively in the market.

Standards have a regulative function, but they're voluntary. Wait — how does that work?

The major unspoken assumption is that the voluntary standard process has to be backed by a competitive market process. The idea is that standards create markets or improve products such that enlightened buyers will prefer standard-compliant products as that prevents lock-in, opens up the network effects of interoperability, etc. And in fact the open standards organisations like the W3C or the IETF tend to reflect the market backing of their decision system, even if in veiled terms: in order to be given consideration, a standard needs to be supported by vendors, deployed at credible scale in real-world implementations, essentially it needs to be viable in the market (even though that word is rarely used).

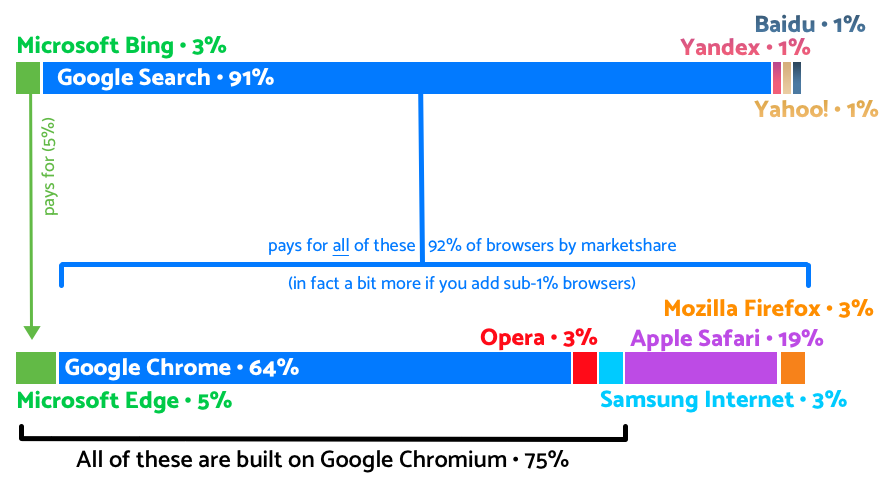

So, say you want to create a new web standard: it needs to be implemented by browsers. The diagram below describes the structure of the "market" that sits behind the "voluntary" process of standards adoption. At the top are all the search engines with more than 1% market share, at the bottom all the browsers with more than 1% market share (both from StatsCounter as of April 2024, the numbers add up to less than 100% because of smaller companies). I list the two together because it is search engines that pay for browsers. So we have Google Search, at 91% paying for every single browser larger than 1% except for Microsoft Edge. And Microsoft Edge (paid for by Bing) is built atop the same Chromium engine, a Google-dominated fauxpen source project. I hasten to point out that paying for a browser does not mean that you get to decide everything that goes into it, but you do get to impose important constraints both explicit and implicit (e.g. in the right to review changes that could impact search, such as privacy improvements).

That's it. That's what "voluntary standards" means on the web. It's voluntary for Google, a little bit for Apple and Microsoft, and everyone else mostly has to live with it.

Let's dig into the problem. "Voluntary standards" are ultimately market-knows-best standards, and given the structure of the market (if you can call it that) there is little reason to have faith that it knows best, if it knows anything at all. Standards organisations aren't exceptional in being structured in this way: this kind of marketwashing of power is typical of global neoliberal institutions. "A common view of neoliberalism describes it as an economic ideology that prioritizes free markets and the liberation of entrepreneurial spirits, and that seeks to restrict the size and scale of government, for example by deregulating. In fact, neoliberalism is better understood as a political order, which generated new patterns of domination via the appeal to a market ideal of freedom. (…) Neoliberalism as a political paradigm seeks less to deregulate across the board than to reregulate in a manner that increases the power of market actors."11 (See also Quinn Slobodian's Globalists for an excellent history of this movement.) In standards, we hear big talk about openness, innovation, and ethics but there is no level playing field on which a better idea can come dislodge entrenched companies or meaningfully hold them to account.

Understanding this market-knows-best dynamic is useful because it points to remedies. Markets are just one kind of institutional arrangement, and considering them to be always good or always bad is about as meaningful as only ever wanting to eat udon noodles or thinking that all housing should abide by the neo-Gothic architectural canon. Part of the answer is that they can be fixed with muscular antitrust action, but another important component is that markets can be influenced and shaped. And, when we say that we want a public interest internet, it unavoidably implies that we need, to some degree, to shape the relevant markets, which in some cases might simply be to make them more competitive from the bottom up. It so happens that there's an existing toolbox for that: industrial policy. The intersection of transnational digital infrastructure standards and governance with industrial policy is challenging but promising. I will return to it more specifically when I describe the global digital architecture.

If the situation is this dire, you may ask why I am spending so much of my time at the W3C? In part because some corners of the process still work, but more importantly because the situation is fixable and I want an operational SDO for the web that is ready for a liberated, rewilded internet. What's more, some important parts of W3C — horizontal review, royalty-free standards, some of the formalism, the centrality of implementation and testing — need to be preserved and propagated. It's an imperfect seed with real potential.

It is an important step forward to abandon the (often unwitting) ideological commitment that leads to voluntary standards, but in order to do so we need to move beyond the false choice between voluntary standards and an ISO or ITU process. (I've seen first-hand in MPEG how those can fail too.) There are other options, and designing them is a big part of the task at hand.

What About Regulation?

We've looked at the power that infrastructural authority grants the tech corporations that have captured it, at how detrimental the consequences of that capture are, and at why the current internet standards system is insufficient to counteract that power. Is this not the point at which we turn to regulation?

Regulation is absolutely necessary, if only because we have no other way to contain the runaway power of big corporations. The state should act as a check on corporate authoritarianism. Historically, that's a mission at which it has too often failed, but there are good reasons to believe that several states around the world are ready to fulfil that function in coming times.

However, regulation alone is not enough. Regulation can constrain but not explore, it can risk fragmenting the planetary internet, and no one has jurisdiction over the full digital sphere. Part of the answer lies in public investment focused on creating direct competition to and disassembling the infrastructural authority of digital giants, though this presents challenges in a transnational context which we need to address.

Working to recover democratic power over the digital requires us to dismantle the platforms' infrastructural power. This requires much more than narrow competition interventions, more than simple trustbusting from above: because infrastructure gives them authority over so much of our lives and societies, the primary impact that digital giants have is through the governance that they provide. "If the digital platforms’ core source of value is the provision of governance services, how exactly would increasing competitive pressures or government-enforced deconcentration benefit societies? (…) In important ways platforms have become the institutional infrastructure of core swaths of the economy. (…) It is this infrastructural role that helps to explain why there is very little public surprise when platforms feel entitled to maintain embassies in ‘foreign nations’."12

It may be autocratic governance, but it's governance all the same. "Digital tech companies have long since abandoned the ambition of being just economically relevant: through the control of public data and their exclusive use of technology they are also agents of the new political order, with their owners often acting as unelected politicians in office."13

That is why, in replacing their infrastructure, the primary difficulty is not technology — that is largely solved or solvable — but governance. How do we articulate legitimate territorial regulation with a unified transnational internet, shaped towards public interest? What properties does such an arrangement need to have? That's the architecture which I turn to next.

Elements of a Global Digital Architecture

David Eaves and Jordan Sandman define digital public infrastructure (DPI) as "society-wide, digital capabilities that are essential to participation in society and markets as a citizen, entrepreneur, and consumer in a digital era." If we look at the internet not as a network (which only describes its implementation) but as the sum total of our connected digital sphere, then a public interest internet is essentially the articulation of all DPI into a planetary open internet system, operating for the public good.

That definition focuses on the function of DPI in society. The fine folks building the India Stack define DPI as: "A set of shared digital utilities powered by interoperable open standards/specifications operated under a set of enabling rules (laws/regulations/policies) having open, transparent, and participatory governance with open access to individuals and/or institutions addressing sovereignty and control built as a set of digital building blocks (not as monolithic solutions) to drive innovation, inclusion, and fair competition at scale." This is a good set of properties (and, interestingly, rather exactly the opposite of what big tech offers). What do they look like extended to the whole of the internet, to all of our shared digital infrastructure, and what governance architecture could support them at that kind of scale? Setting the actual technological details aside for now, three broad design questions emerge:

- How to articulate the global with the local?

- How to govern the various parts of the system competently, effectively, in the public interest, and so as to support greater human flourishing?

- How can we realistically make this happen, and sustain it over time?

Let's address these in turn.

Planetary and Local

The internet is a transnational public good. Being transnational and public at once is tricky because we lack a definition of public that isn't tied to territorial government. Worse, to some extent setting rules at the transnational level may conflict with democratic preferences expressed at more local levels, and has the potential to undermine the public (and public interest) potential of the internet. Conversely, territorial rules that apply to the digital sphere can in some cases limit global interoperability, leading to a splinternet. Our architecture needs to balance the two, to organise both territorial state and transnational components so that they work best together, in the public interest, and the model needs to work without requiring all states (or even many, to start with) to initially agree to participate. This section details seven overlapping considerations that explain how to articulate the transnational and the territorial, and why.

A good starting point is that polycentric tension is good, actually. As we have seen, separating technical standards and internet governance on one side from politics and policy on the other is an implicit commitment to neoliberal preferences in which market dominance is the only legitimate source of power. It removes the politics from standards-making, when the politics in fact belongs right there. If different types of institutions — here territorial states and transnational bodies — have partly overlapping responsibilities, they can serve as checks and balances on one another as well as complement each other in legitimacy. So we should design with polycentricity. (If you've read The Internet Transition and Stewardship of Ourselves, you won't be surprised to hear that I support greater institutional density.)

A second consideration is that we benefit from transnational shared infrastructure with global addressability and interoperability. Technologists tend to take this for granted, but the oppressive nature of the current infrastructure is leading many people to long for a dark forest approach to the internet, in which they can join a small disconnected island they trust and be minimally exposed to the rest. But we can address their legitimate concerns while maintaining a global system. Digital infrastructure is complex and easy to get wrong, we gain a lot from sharing it, and that's before mentioning the benefits learning, connecting, collaborating, and governing across borders.

The global digital sphere is worth preserving even as we strengthen local power. Strengthening local power in fact increases the value and effectiveness of shared infrastructure at planetary scales because we get more resilient and more capable systems when we push the intelligence (and therefore the agency) at the edges — so long as local variations do not break global invariants.

When we say that we want the internet to work in the public interest we necessarily say that we want to shape how technology works beyond devolution to the market. That shaping happens differently in transnational or territorial contexts.

In a transnational context, this shaping is my third mouthful of a point: capabilities-centric infrastructure neutrality. Let me unpack that a little.

As explained above, infrastructure is neutral when 1) there are constraints on infrastructural authority, for instance thanks to the system being governed by infrastructure users and 2) its operators do not make use of intelligence gathered from operating the infrastructure, particularly not for optimisation purposes.

However, since no technology or infrastructure is ever fully neutral, we need to select a bias that is defensible in a system that is shared by all of humankind. I believe that that bias is adherence to the capabilities framework, a concrete approach focused on agency. (I discuss capabilities in tech at length in The Web Is For User Agency and refer you to that piece for details.)

From an oversight perspective, infrastructure neutrality focused on capabilities can be enforced by empowering what in internet standards is known as "horizontal review." Horizontal review groups are groups that specialise in a specific property that applies across all areas of technology, such as accessibility, internationalisation, privacy, security, interoperability, or architectural coherence. Even though I would expect each infrastructure component to have its own governance (see below), its decisions would need to be validated by horizontal review groups (as is the case in W3C today, if incompletely) and the decision process of HRGs would focus on capabilities, coherence, and infrastructure neutrality.

In territorial contexts, shaping the internet follows a more established approach, the fourth point: enabling industrial policy.

"Industrial policy is best understood as the deliberate attempt to shape different sectors of the economy to meet public aims."11 Evidently, that is directly aligned with what we wish to do. In addition to globally shaping infrastructure in support of human capabilities, ensuring that territorial states need retain meaningful authority introduces diversity and (imperfectly) increases the odds of aligning infrastructure with its users. Pragmatically (for my more anarchistic friends) such a global digital architecture cannot successfully be created against the states. However, evident as the alignment between a public interest internet and industrial policy is, the question is complicated by the interaction between territorial industrial policy and transnational standards.

Internet technologies are a challenging target for industrial policy or public investment. If one country invests in digital infrastructure (say, in open source security which is woefully underprovisioned), then all the other countries benefit from that investment too. While that's a desirable property of a commons, it does lead to free riding which can make it difficult to justify the expense to taxpayers, especially if it is to be sustained persistently (as it does).

Additionally, when one country provides digital infrastructure that is used globally, the ways in which it shapes that infrastructure and the dependencies it introduces increase the risk of digital colonialism.

Because of this, while I'm very excited to see a growing number of state-led DPI projects such as the German Sovereign Tech Fund or the India Stack — those people are doing a lot of the right things — because there is a sore need for this kind of investment and those moves are the right ones given our current captured infrastructure, I am equally eager to see transnational infrastructure being funded and governed transnationally and territorial funding primarily refocused onto local concerns.

Effectively, the articulation between these two approaches to shaping the internet in the public interest are that transnational infrastructure neutrality enables territorial industrial policy against a human-centric background; and conversely territorial industrial policy must be careful not to break infrastructure neutrality. This can be conceived of as a form of public/open partnership in which the coordinated articulation of regulation and technology produces better outcomes than the sum of their independent action. Additionally, giving infrastructure neutrality a capabilities orientation ties well with industrial policy because capabilities are inherently developmental14 and "we should view industrial policy as a developmental practice: it involves deliberate attempts to shape sectors of the economy to meet public aims writ broadly, rather than to serve values of wealth-maximation or national competitiveness."11

Extending on the mention of digital colonialism above, my fifth consideration is that this global digital architecture needs to support sovereignty from. Countries around the world are increasingly (and often rightly) worried that their infrastructural interdependencies, particularly digital, can be weaponised against them.15

Such concerns are legitimate: the dependencies that states and swathes of the world economy have on actors that are concentrated in the US is terrifying to anyone who understands both the power of infrastructure and the state of American politics. But the manner in which states react to this concern is not always optimal. As Meredith Whittaker put it in Cristina Caffarra's excellent recent Public Interest Digital Innovation event, "Europe doesn’t want to be so dependent on US giants, but often the aspiration takes the form of 'we want what they have but ours' – that’s a terrible idea. AI is a derivative of centralized surveillance, it’s not magic, not God, it’s pattern recognition across massive amounts of surveillance data owned & processed by a handful of US-based actors. You don’t want a 'European AI' if that’s what it is, don’t want to throw money at NVIDIA just so you can have a French stack, a German stack... You want computational technology that serves democracy, a liveable climate future, resources accessible to every human."

Altogether too often, states approach digital sovereignty by building their own corner of cyberspace in such a way that they can make traditional claims of sovereignty over them. But we don't want a French cloud and a Kenyan cloud and a Thai cloud and an Ecuadorian cloud and… The duplication is wasteful and the fragmentation maddening — and neither is necessary.

Sovereignty from is what you obtain when your infrastructural (inter)dependencies are managed in a way that guarantees the true independence that enables one to exercise sovereignty. Put differently, sovereignty from is the international relations result of infrastructure neutrality. States need to treat internet governance organisations and their outputs as essential to their sovereignty and require them to govern our shared digital infrastructure in ways that secure states against weaponised interdependency. That is one aspect of the wider digital non-aligned movement.

A sixth consideration (hang in there Dear Reader!) is that this architecture enables subsidiarity and experimentalism. Our global digital sphere can have enough real, enforceable values as part of its infrastructure neutrality that it can be cohesive, have a positive impact on humankind, and support public aims, but also support the inherently plural nature of global humankind.

Subsidiarity is the principle that a central authority — here the global internet — should perform only those tasks which cannot be performed at a more local level. Global interoperability requires more than purely technical considerations — as we have seen, infrastructure neutrality remains biased albeit in ways that support system resilience and human flourishing — but it should not dictate the minutiae of what can be done locally. We can consider the result to be akin to a splinternet that still interoperates, a multi-model/multi-polar internet. Infrastructure that makes space for subsidiarity (emphasises sovereignty from) can be achieved by enforcing strong, protocol-based rules and governance models that help prevent the accumulation of power. (Note that supporting human capabilities means that we cannot compromise on key aspects such as privacy and security, which means for instance that at the internet level we must rule out encryption backdoors or chat scanning. Capabilities map to human rights, and these are not subject to subsidiarity.)

This approach works well with experimentalist governance. Experimentalist governance learns by iterating on initiatives that are scoped both geographically and temporally, and then applying positive findings to wider scopes. "A secular rise in volatility and uncertainty is overwhelming the capacities of conventional hierarchical governance and ‘command-and-control’ regulation in many settings. One significant response is the emergence of a novel, ‘experimentalist’ form of governance that establishes deliberately provisional frameworks for action and elaborates and revises these in light of recursive review of efforts to implement them in various contexts."16

Within a problem space in which we benefit greatly from response diversity and need to recover the resilience that we have lost to monopolies, "[e]xperimentalist governance can be understood as a machine for learning from diversity. It is thus especially well-suited to heterogeneous but highly interdependent settings."16 It has been deployed successfully in numerous sectors, from energy to finance or telecoms to environmental protection.

Note however that the European privacy regime has demonstrated the risks that can be associated with experimentalist governance as it has enabled the Irish data regulator, the DPC, to single-handedly undermine the GDPR. While experimentation must be enabled, channels to challenge it are necessary.

And the final consideration I will bring to this topic is that the governance bodies in charge of transnational infrastructure must be sectoral. No one wants a unified UN of the whole internet. A unified institution will invariably be complicated and risks unnecessary interference between different branches. "To adopt a sectoral lens is also to accept that the size and operation of individual sectors matters, because institutions do not inevitably adapt fluidly to market signals, equilibrating across the whole economy."11

Having a multiplicity of specially-crafted institutions isn't all that unusual. "When one thinks of government, what comes to mind are familiar general-purpose entities like states, counties, and cities. But more than half of the 90,000 governments in the United States are strikingly different: They are “special-purpose” governments that do one thing, such as supply water, fight fire, or pick up the trash."17 One benefit of special-purpose institutions is that each can have its own governance model that is tailored to its specific needs. We shouldn't expect a search infrastructure institution to have the same governance as a the advertising infrastructure institution, which in turn would differ from the one handling browser infrastructure.

One challenge is of course to keep those coherent where they overlap and integrate, which is often. That is enforced by yet another special-purpose institution, tasked with the horizontal review norms that guide all of these systems.

Effectively, the answer here isn't world government, but it might be lots of special-purpose world governments with limited scope and powers.

So I have outlined what to consider when building a system that can work in the public interest, that respects plurality while operating at a transnational scale. But I've treated the relevant institutions, those planetary special-purpose governments in charge of components of our digital infrastructure, as black boxes, without specifying what they are or how they work. I turn to that next.

Democracy Harder

Governance is about deciding, evidently, but also about doing. Organising an institutional arrangement that can make the best of decisions yet do nothing about them would be an exercise in futility. Yes, we need democratic control over our essential digital infrastructure, but rather than deciding how to implement democracy first (e.g. people vote!) and then hoping we can make it work somehow, I am proceeding in the opposite direction: defining the broad kind of institution I believe that we need for each infrastructural domain, and then working out how to make it increasingly democratic over time.

What I envision is that each broad infrastructural domain — e.g. commerce, social, browsers, search, advertising — ought to have its own special-purpose institution. Those institutions would be a blend between an independent administrative agency and a self-regulating organisation (guaranteeing almost instantly that everyone will hate the idea):

- Administrative because action-biased, focused on doing, but nevertheless with some checks and balances since you don't want critical infrastructure to go off the rails.

- A form of self-regulating organisation because it's transnational, which means there is no state to provide oversight and an SRO can provide that framework. Note that I am emphatically not thinking about the kind of SRO in which only the infrastructure providers would be represented, or in which they would dominate. The stakeholders who rely on the infrastructure would be represented, with real power.

This kind of institution would generally not provide the infrastructure directly (in most cases you don't want just one global provider) but would govern (with some degree of subsidiarity) how other actors (private or public) do that. This may at times require interfacing with territorial states, for instance on points of scaling or enforcement — something that I think of as public/open partnerships. One way to think about these institutions, if you're familiar with internet governance, is as beefier standards organisations. Their remit includes standards but also includes arbitration, taxation, and (as rarely as possible), the power to sanction (for instance by excluding from participation).

Note that when I say that these organisation "govern" the infrastructure, that is with relatively limited power and interventions. "Governance in this context refers to the wide array of institutional means by which communities make decisions, manage shared resources, regulate behaviour, and otherwise address collective action problems and other social dilemmas."18 The goal is to ensure that the infrastructure operates smoothly, according to the principles that the institution is chartered to uphold, but not to exercise executive control over day-to-day operations. The chartered principles need to vary between domains, but always need to support infrastructure neutrality and a capabilities approach.

It is evidently crucial that such an institution not become captured, and more generally be maintained in such a way that it continues to align with public interest over time. One of the ways in which this happens is by having special-purpose institutions monitor one another, to maintain sufficient alignment, with the power to intervene collectively under some conditions. Another is that stakeholders of different kinds, including underrepresented ones, must have a genuine say. "Public power is not a concentration of authority, but a network of reciprocal relations."11

But, more generally, the problems of how to govern an institution with this kind of power and goals over time are similar to those involved in governing an administrative organisation tasked with the deployment of democratic industrial policy. The bad news is that "we lack a theory of how to collectively realize this new economy, in a fashion that is durable, effective, and democratic."11 This further includes the risk of repeating the antidemocratic structure of transnational bodies such as the IMF or the WTO. But administrative authority over our global digital infrastructure is an unavoidable condition of public power, and challenging as it is to render it accountable and democratic, it's easier than it is for transnational corporations.

While we may lack a fully integrated theory, democracy provides us with a wealth of experience which we can refine over time. As Audrey Tang puts it: "Democracy is a social technology that improves when people use it." Gráinne de Búrca further encourages us to strive to iteratively improve democratic control precisely in this kind of setting. I cite her in full because I couldn't have put it better:

There is an extensive and growing literature on the dilemma of the democratic (il)legitimacy of transnational governance. I have grouped the range of responses to be found within this literature into three broad categories. The first I call (a) the denial approach: the claim that there is no “democracy problem” in transnational governance; the second (b) the wishful-thinking approach: the assumption that transnational governance is either sufficiently democratic or that it can readily be democratized; and the third (c) the compensatory approach, covering a wide range of positions which argue that transnational governance cannot practicably be democratized and that its legitimacy, if any, must be grounded in other sources. (…) I propose a fourth alternative to the three described above which will be called (d) the democratic-striving approach. The democratic-striving approach acknowledges the difficulty and complexity of democratizing transnational governance yet insists on its necessity, and identifies the act of continuous striving itself as the source of legitimation and accountability.

We live in a time of disillusionment with both democracy and technology. Disillusionment is a time for hope and renewal. The first thing that most people think of when they consider democracy is electoral representation: once in a long while you vote for people who are then supposed to conduct the business of the community in our name. But that was the 18th century's approach to democracy — we can do better. Electoral representative democracy isn't even all that democratic to begin with.

What is it that we strive for when we strive for democracy? I would expect each one of these special-purpose institutions to have its own governance matching its specific problem space, but we can consider two things: at the conceptual level, metademocratic principles to build towards in transnational neutral infrastructure, and at the practical level, examples of newer approaches.

If you were to read only one book on democracy in your entire life, I would recommend you pick Danielle Allen's Justice by Means of Democracy. I couldn't possibly summarise her many excellent points here, but I will pick up a few strands that I hope can stimulate our thinking. My intent in this section is not to (re)produce a theory of democracy but rather to show that we can both think and experiment our way out of our antiquated mental models.

I have advocated for a capabilities framework above and that approach is directly linked to justice and flourishing, which also lines up with Allen's thinking: "justice consists of those forms of human interaction and social organization necessary to support human flourishing."19 This guides institutional design: "Our beliefs about justice translate into design principles for human social organization and behavior, and these in turn are operationalized in concrete laws and social norms."19 It's useless to have values unless you also operationalise them through your governance, and so as we strive for just infrastructure we continuously seek to improve our governance arrangement, in great part by experimenting with new approaches.16

Allen develops a framework of design principles which we can reflect in our institutions. These include:

- Not sacrificing both negative and positive liberties. Negative liberties such as freedom of speech or of association permit us to chart our own course without interference. Positive liberties permit us to participate in the institutions that govern our lives as authors, as having voice.

- A commitment to equality. Egalitarian participation is not defined by majority vote but by mechanisms of participation that give people control over collective decision making. This means a focus on limiting power imbalances and being actively resistant to capture: "The surest path to justice is the protection of political equality; that justice is therefore best, and perhaps only, achieved by means of democracy; and that the social ideals and organizational design principles that flow from a recognition of the fundamental importance to human well-being of political equality and democracy provide an alternative framework."19 Systems like W3C voting that have one-member/one-vote but that don't counterbalance actual market power over decision-making do not meet this commitment, but minority-protecting mechanisms such as horizontal review for accessibility, internationalisation, privacy, or security are key (to the extent we make them enforceable).

- Difference without domination. We have a paradox to resolve: if we support freedom of association and of contract people will create social difference either through business or other institutions. Difference is good (even essential) but it also enables domination. "How can we protect rights and foster the emergence of social difference yet avoid the articulation of that difference with structures of domination?"19 The implementation is to systematically, constantly, and defensively monitor for the emergence of domination and to tweak the relevant institutions to compensate. A world without domination can still have hierarchy and constraints — provided they're legitimate.

Abstract as this may seem, this short framework (and Allen's much fuller development in her book) already provides guiding notions to help discuss how we should organise. And many projects have been exploring just that, at a variety of scales. Nate Schneider has written about how essential these experimentations are and describes how the internet can learn from governance that has existed to become more democratic in Governable Spaces. (Another excellent book on democracy — I never said there should be only one!)

The past couple of decades have seen the rise of democratic innovations, including some noted successes of citizens' assemblies. While we don't have a cookie-cutter template for renewed democracy in digital spaces, we have a lot of material from which to work. This can be seen for instance in Hélène Landemore's work to define open democracy as well as with the emergence of deliberative tooling such as Pol.is (see notably this presentation from Colin Megill, notably the segment on how Taiwan regulated ride-hailing apps). The space is maturing enough that people there are working towards standardising interoperability between deliberative tools. Another element in the toolbox is the global coops.

With an experimentalist mindset, each institution can drive ways of extending democratic power and accountability, and we can trade successes between institutions. Don't get me wrong: it will be imperfect and messy; but we can do better with every new iteration. It beats hoping that corporations grow the right ethics or that regulations find the exact right incentives.

These are the democratic building blocks. It's good to know that they exist intellectually and have been implemented in some contexts, but democratic buildings blocks aren't sufficient on their own to build the full global digital architecture of a public interest internet. Is it really feasible?

For Real

Several things need to be true for this architecture to be credible:

- It needs to have momentum, notably political momentum with policymakers and interest from implementers.

- It needs money or the ability to direct money towards infrastructure providers governed by the system.

- It needs to be enforceable.

- There should be existing examples of similar arrangements, at least for part of the picture.

I am writing this today because I believe that we have these elements, and we need to move to execution and working out deployment in detail.

First, I see a public interest internet as having momentum with the architecture outlined here because the world isn't headed in a direction in which governments are comfortable relying on infrastructure provided or controlled by other governments, or by companies that could easily be controlled by other governments. Nor should they be. I mentioned Meredith Whittaker pointing out the massive reliance of governments on infrastructure provided by US companies; a similar dependency can be observed in media companies20. Just trying to threat-model what a second Trump administration could do here ought to be enough to kick anyone who understands the power of infrastructure into action. We need to switch to a model of mutually assured interdependence, of sovereignty from, which this architecture provides a blueprint for.

Additionally, we are witnessing a return of the strategic state, the project state, and of the industrial policy that goes with. Today's captured infrastructure stands in the way of industrial policy, it forecloses too many options, seizes too much in rent. An architecture, such as this one, designed to support industrial policy is desirable.

And antimonopoly is no "side dish" to a successful industrial policy, on the contrary it is an essential component. No amount of investment to strategically shape the digital sphere can succeed if it is entirely locked down by big technocracies. This architecture is designed to break down concentrated power and to help support market-making from the ground up, directly challenging the power of established tech rather than just intervening with antitrust operations from above, often too late and always too little. This growing antimonopoly movement is a democracy movement seeking to redistribute power in society, beyond just antitrust.

Second, there's money. In fact, there's plenty of money. Remember the Metaverse? Facebook lost $20bn developing it just for 2019-21 (losses continued into 2023, but I tired of seeing low-quality 3D graphics looking for the numbers). There's money for infrastructure, our job is to make it flow towards the public interest rather than to random billionaire fixations.

Similarly, some amount of money in the $20-50 billion range is being levied from search engines and handed over to browser companies every year. That's a lot of money, and very little of it goes to actually making browsers better or to supporting a better web — on the contrary, a lot of it is used to compete against the web. I am developing a proposal (WISE) (still in its very early phases) to replace the existing informal, privately-controlled taxation system with a formal, open, democratic, public interest one. The value of search comes almost entirely from the public sphere at large and should return to the public sphere, it should support its infrastructure. This could be instrumental in building the institutional capacity required for this global architecture.

Stephanie Stimac recently gave a talk at Web Engines Hackfest 2024 that provides a great introduction to how parts of the web community are thinking of tackling this. Previous discussions of the same topic had already been covered on Brian Kardell's blog based on an event we organised, as well as on a podcast with Brian and Eric Meyer. Other funding efforts are also afoot, as readers familiar with Funding the Commons will know.

And that's only search/browsers. I have an earlier proposal to support the governance of advertising infrastructure in the public interest (GARUDA) that includes a funding component. (I would not set up its governance that way today, but the overall idea stands.) We can devise similar, very lightweight systems for social or commerce for instance. To give an example, Beckn's ride-hailing system finances its infrastructure (which is privately provided but using open protocols) with a very simple flat fee. The ease with which one can become a Beckn provider ensures that fees stay low.

Third, we can develop means of enforcement. One useful way to look at this is Dave Clark's Control Point Analysis2122. "Control point analysis proceeds by listing the steps of common actions (for example, retrieving a Web page), and asking at each step if one has encountered a significant point of control."21 Clark starts (rightly) all the way at device selection and goes through each step involved in an action to list all the points at which capture can take place. These control points are how corporations build power and capture infrastructure. (In 2012, he already listed Google as injecting itself at a long list of control points.)

The enforcement method I propose is to pick control points which we put under the authority of an infrastructure institution. For instance, one option for the WISE proposal is to control the setting of default browser and search via choice screens and OS settings. (I am well aware of issues with choice screens, but that's a discussion for another post.) A choice screen operates by having a list of eligible choices (browsers or search here). The institution would only accept membership in that set for participants who abide by its rules, including here participation in the levy. Authority over a control point is unlikely to be simply yielded, it would likely have to be the work of a regulator. But such regulation is simple: it mostly delegates oversight to an institution that then needs to abide by its mission. The regulation also need not be passed in every jurisdiction: a single major jurisdiction would suffice (for participants that intend to have a meaningful global footprint at least), and then the institution's rules can dictate that its rules must be followed worldwide.

In a similar vein, the GARUDA proposal could be supported via ad blocking: to avoid blocking, ad infrastructure providers would have to abide by a set of rules (privacy, transparency for publishers and buyers, ad performance, etc.).

The general goal here is to use regulation as a scaling factor for collective innovation, by giving an organisation a mandate to keep infrastructure neutral, to make domain-specific rules that support capabilities and an active, innovative market.

Finally, I do believe that there is evidence that this kind of collective approach is feasible and has been achieved. Some of the papers I cite, such as on special-purpose governments17 or on experimentalist governance16 provide lists of concrete cases, at scales big and small. Erik Nordman provides examples of transnational commons outside of the digital space23.

We also tend to forget it, but Wikipedia is essentially a bureaucracy that produces an encyclopaedia. It is imperfect, but it has succeeded at a difficult task and its approach to subsidiarity in language is worth keeping in mind.

Proposals like WISE or GARUDA are not reality, but it's noteworthy that the CMA Privacy Sandbox 2024Q1 report mentions "governance" dozens of times to point out that there is no clear proposal on the table. The expectation is real.

In a particularly challenging space — content moderation — Bluesky's Ozone system shows that the basic mechanics that can support collective CoMo work-sharing are possible. I would also point out that GPC provides a great example of policymakers and technologists collaborating, with the former providing a simple framework and the latter filling in user-centric details.

I am particularly excited by the leapfrogging we are seeing from projects such as the India Stack or Brazil's Pix. The sheer scale of these systems and the social innovation they support show that focusing on infrastructure structured around protocols rather than rent-seeking has huge promise.

The Digital Sphere: A Planetary Commons

From the redistributive societies of ancient Egyptian dynasties through the slavery system of the Greek and Roman world to the medieval manor, there was a persistent tension between the ownership structure which maximized rents to the ruler (and his group) and an efficient system that reduced transaction costs and encouraged economic growth. This fundamental dichotomy is the root cause of the failure of societies to experience sustained economic growth.

— Douglass North, Structure and Change in Economic History

I never promised that this would be easy. I am keenly aware that several of the ideas presented here are so far outside the Overton Window it's an open question whether they're even on the Overton wall by the window. For all we know they might be down the road adorning the Undertons' house. We are talking about governing infrastructure for over 5 billion people; 8 billion within our lifetimes. It should be complicated.

But we should evaluate this architecture against the alternative we have. We could keep our digital infrastructure entirely in the hands of a few megacorporations and decide to endure through more of what we're seeing today. We could try to mitigate some of that with purely extrinsic, territorial regulation and hope that our governments not only succeed with this often blunt and indirect instrument but also somehow remain independent from the influence of those corporations when they own and operate the informational infrastructure of government itself. Having seen how that's working out for journalism, do we want the same for the rest of democracy?

Internationally, we have four recognised global commons: the high seas and deep seabed, outer space, Antartica, and to some degree the atmosphere. All of these have issues with their governance, but they are a step forward. As we face the critical challenges of the coming few decades, we need to begin thinking about upgrading global commons to properly planetary commons24, and internet infrastructure understood broadly should be one of them. Without coordination we won't solve the climate and biosphere crises, and with captured infrastructure we cannot coordinate in intelligent and resilient ways.

When you have power, democracy can be a bit of a nuisance, and those of us who care about democracy have competition in designing this global digital architecture: a coalition of today's most powerful — including Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon — is working to insulate themselves from the vagaries of democracy, with temporary success under Trump. They seek to make sure that precisely that kind of popular, people-centric regulation cannot be put in place, no matter how much democratic support it may garner. They are doing this through "digital trade" provisions in international treaties that would preempt the domestic regulation of tech. As Joe Stiglitz writes in Foreign Policy: "Big Tech’s trade-pact ploy is to create a global digital architecture where America’s digital giants can continue to dominate abroad and are unfettered at home and elsewhere. (…) In pushing for particular rules in international trade agreements, the lobbyists are trying to foreclose debate, arguing that any government intervention, including those actions designed to promote competition and prevent digital harms, is an unfair and inefficient restraint on trade. The result of this backdoor strategy, were it successful, would be to constrain the U.S. government — and its [trading] partners — from adopting and enforcing privacy, data security, competition, and other policies in the public interest."

Rather than wait and hope, we need to proactively define a vision for a better global digital architecture and start implementing it. My here point is that this alternative, democratic future is rooted in digital public infrastructure and its governance, and that we have the building blocks to make it happen. I hope you'll join my friends and I in working on it.

The future isn't about flying cars. Where we're going, we're gonna need roads.